If Motown: the Musical, the latest jukebox show to hit Broadway, had had a good book, instead of the anemic and self-serving one written by Berry Gordy, it would be a powerhouse. Still, thanks to that music, which to me is among the greatest of all time, Motown is one immensely entertaining evening that sent me out of the Lunt-Fontanne filled with joy and memories.

The show, directed with little imagination by Charles Randolph-Wright, is drawn from Gordy’s 1994 autobiography, To Be Loved: The Music, The Magic, the Memories of Motown, about the creation of his pioneering music labels, most notably Motown. Gordy presents himself in a far kinder and milder light than that of Curtis, the Gordy figure in in the far better written -- and by all accounts except Gordy’s, more accurate -- Dreamgirls. (Gordy is also one of Motown’s producers.)

That’s one of the biggest problems of the show -- no conflict. At 29, after being a failure at every job he’s had, Gordy (Brandon Victor Dixon) borrows money from his family to start a recording company, which becomes the empire known as Motown (a name derived from Motor City, the nickname for Detroit, his hometown) and would launch the careers of some of the best singers and groups of the 20th century -- Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, The Temptations, Diana Ross and the Supremes, Stevie Wonder and Michael Jackson, to name a few.

Act One shows this unfurling with nearly miraculous ease -- Gordy discovers talent after talent, records are turned out rapidly and all become hits that are accepted on white radio stations as well as black. It’s all too simple and courteous. Dreamgirls (book and lyrics by Tom Eyen) brought out the ruthlessness of the record mogul and the back-stabbing behind the “girl group” he founded, which was based on the Supremes. It portrayed the fight for acceptance, the dirty dealing of other groups in stealing songs and the betrayal of love in that high-stakes showbiz environment.

Gordy also could have taken lessons from Marshall Brickman and Rick Elice on how to write a strong book for a jukebox musical about real people. Their Jersey Boys tells an involving story about the lives and career struggles and successes of Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons. So it can be done.

The trouble is, Gordy seemed to want to take on the whole Motown history. Even in a show that is two hours and 40 minutes long, that’s not enough time to do more than give a passing nod -- if that -- to the stories of these performers. With more than 50 songs, Motown seems more like a Greatest Hits concert than a Broadway musical.

By the second act, though, I no longer cared about knowing the full story behind the songs because the songs were the story. That’s the music I grew up with in the 1960s and 70s, starting in elementary school when we used to line dance to the Temptations. I carried my transistor radio with me everywhere -- out with friends, to the swim club, the beach, baby-sitting and into my bedroom at night. I listened every waking moment I could.

That’s why Motown was so appealing to me, because it was the soundtrack of my youth, the way the songs of the Hit Parade were for my mother. Music that is so interwoven into our lives will always touch a deep cord. I remember being on the Underground in London in 1984 and seeing a headline on a tabloid across the aisle announcing that Marvin Gaye, a Motown genius, had been fatally shot by his father. I was devastated.

I felt an emotional response in the show when the young Michael Jackson (Raymond Luke Jr. in a standout performance) was introduced to Gordy. It was sad to remember what a fireball of talent he was then, and remained right up through “Thriller” in 1982, but what a pathetic -- and sick -- figure he became.

Motown only goes as far as 1983, using the framing device of the 25th anniversary TV tribute to the company, its founder and its artists. At the start, Gordy refuses to go, bitter is he that so many of the stars he discovered have moved on and his company is in steep decline, unable to compete with the mega-million dollar contracts conglomerates like RCA can offer. By the end, after recounting what here seems like a breezy road to success over two decades, Gordy relents and joins his superstars on stage for the happy ending.

I liked Valisia LeKae as Diana Ross. Her speaking voice sounds amazingly close to Ross’ breathy, little girl voice, and I especially liked her “Reach Out and Touch” number that had her singing with volunteers from the audience and ended with all of us holding raised hands with our neighbors, swaying and singing along.

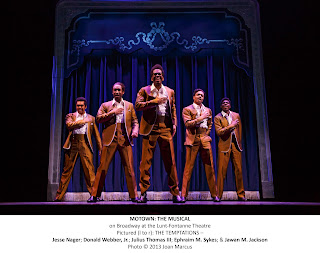

Charl Brown as Robinson and Bryan Terrell Clark as Gaye were also strong, even if their characters seem more like bit players in this musical that is trying to fit in so much. The ensemble members were good as they came and went quickly, dancing the steps made famous decades ago by the likes of the Temptations and now choreographed by Patricia Wilcox and Warren Adams. Esosa did a smashing job with costumes, David Korins needed more pizzaz in his sets.

I’m not alone in liking Motown, flaws and all. It is one of the top-grossing Broadway productions of the season, playing to sold-out houses, and, according to Playbill.com, grossing upwards of $1 million weekly for all four weeks of its preview period – a record for any Broadway show to arrive in New York without an out-of-town tryout.

(Photo, by Joan Marcus, of the Temptations, played by Jesse Nager, Donald Webber ,Jr., Julius Thomas III, Ephraim M. Sykes and Jawan M. Jackson.)