Saturday, August 23, 2014

St. Mark at La MaMa, an unlikely combination

I wrote this feature for the Sept. 7, 2014 issue of The Living Church magazine.

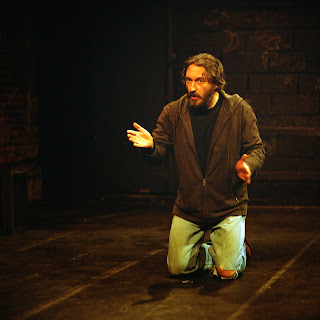

Lights flash in the darkness as a middle-age man in a gray hoodie, jeans torn at the knees and a backpack slung on one shoulder runs into the deserted alley and hides behind a trashcan. When he feels the coast is clear, he walks to the back wall and chalks a fish on the black bricks. Then, with excitement spilling out of him for the good news he wants to share, he throws out his arms and begins to tell the greatest story ever told.

This street artist is actually actor/director/Jesuit priest George Drance, 51, presenting his latest work, *mark, a performance of St. Mark’s gospel from start to finish at La MaMa, one of New York’s most esteemed Off-Broadway theaters. Although it would seem an unlikely show for the hip Greenwich Village theatre, Drance has received more enthusiastic response for this than from anything else in his fruitful career. Some people have seen it two and three times.

“What they’re saying consistently is it’s like they’re hearing it for the first time,” Drance said. “They’re surprised by the words they thought they knew. Something about the power of a complete narrative allows a connection to be made.”

Sitting on a bench in an outside courtyard on Fordham University’s Manhattan campus, where Drance is an artist-in-residence, he recalled the spark that inspired the 12-performance run this spring. Joanna Dewey of the Episcopal Divinity School was team teaching a course Drance was taking at the Jesuit’s Weston School of Theology in 1993. She stressed that Mark was meant to be recited. The actor in Drance perked up.

“I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to be part of that tradition?’”

Contemporary New York is a far different time from when Mark’s gospel was written, an era when followers of “the Way” were brutally prosecuted by Roman Emperor Nero, but Drance thinks the present day has a different need for the message.

“I have to confess a little sadness about how the gospel is made marginalized in contemporary culture. It seems irrelevant to many and at best just quaint.”

A street artist seemed an appropriate representation, Drance says, because they communicate in the same kind of “underground” way in which the gospel was first presented. He wanted to “recapture the danger, yet with hope; the challenge, yet with love.”

A resident artist at La MaMa, Drance had booked space there two years ago to do a show this spring. As the artistic director of Magis Theatre Company, he knew he would have a show ready, just not which one. Magis recently launched the Logos Project, which examines sacred performance in all the world’s traditions, creating seminars, workshops and, with *mark, a first full performance. With La MaMa underwriting most of the major costs and with the support of Magis’s funders, Drance saw the gospel in action.

“The gospel is about community and although it’s a solo show, there’s a huge community behind it.”

In transforming this gospel — all 13,000+ words of it — as theatre, Drance follows in noble footsteps. The great British actor Alec McCowen won praise around the world for the one-man play he devised, St. Mark’s Gospel, which earned him one of his three Tony Award nominations when he performed it on Broadway. Drance, who has performed and directed in more than 20 countries on five continents, never saw McCowen’s performance live but has watched some scenes on film.

He began preparing for his version in Advent by listening over and over to Mark’s gospel on an audio file of the New Testament his sister had given him many years ago. Then he began to speak along with the recording before creating his own pastiche of “NASB, NIV, Interlinear and a few other translations that grapple with the Greek.”

In Lent he started working with his director, Luann Purcell Jennings, and on Good Friday went to Union Square Park in Greenwich Village to recite the passion at noon. A few people stayed to listen, others kept their distance but looked on. He opened his 12-show run on Ascension Day.

“The biggest challenge is to get out of the way and trust that the work has already been done and the rest is up to the Spirit.”

Although he met this challenge without a prompter in the wings, he did, in the context of the street artist, have three columns of “hyroglifics” on a side wall with symbols representing the different stories he was recounting. To prepare for each 100-minute performance, he read the text once during the day in the chapel at his West Village residence. When he got to the theatre, he walked through the set and then spent time in quiet and prayer.

He chose to portray the gospel through a street artist because as he thought about the early Christians, the image of their graffiti kept coming up — the crosses and ichthus (fish). He added the six-barred asterisk representing Jesus’s name in Greek, with the I superimposed over the X. The lower case “m” in the title represents Drance’s love of e.e. cummings.

“The asterisk with the ‘mark’ is a play on words. What mark do I leave behind and how am I marked by the gospel story?”

When he first planned to perform the gospel, he hadn’t thought ahead to using music to underscore the action, but when he mentioned his intention to his good friend Elizabeth Swados, an intentionally acclaimed composer and Tony nominee, she said she wanted to write the music. Drance describes her score as having “an ancient soul but with a contemporary voice,” through piano, synthesizer, bass and guitar creating city sounds of cars and machinery using an electronic base, with some light and acoustic variations.

Drance is hoping a producer will take over the show for another run or that he can tour with it. Its message for audiences today is “the ways in which we’re afraid to be light and salt and the ways we’re afraid to tell the good news. This is one way of encouraging people that this is still good news and that there are a million ways of telling it.”

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment